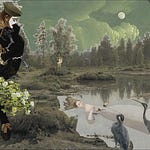

XLVII. LE MIROIR

D’un croissant de lune hilarante S’échancre le ciel bleu du soir, Et par le balcon du boudoir Pénètre la lumière errante.

En face, dans la paix vibrante Du limpide et profond miroir, D’un croissant de lune hilarante S’échancre le ciel bleu du soir.

Pierrot de façon conquérante

Se mire — et soudain dans le noir

Rit en silence de se voir

Coiffé par sa blanche parente

D’un croissant de lune hilarante !

XLVII. THE MIRROR

TA crescent of laughing moon cuts itself out of the blue evening sky, and through the balcony of the boudoir the wandering light pushes in. Across the room, in the vibrating peace of the clear deep mirror, a crescent of laughing moon cuts itself out of the blue evening sky. Pierrot playing conquistador gazes at himself—and suddenly, in the blackness, laughs silently to see himself coifed by his white foster mother with a crescent of laughing moon!

NOTES (by line number, starting with the title)

2 hilarante : Hilarious, laugh-inducing. DAf1878 : « Qui excite à la gaieté. Il ne s’emploie guère que dans cette expression, Gaz hilarant », ‘Which excites gaiety, hardly used other than in the expression laughing gas’. Soon after Sir Humphrey Davy discovered in 1799 (by self-experimentation) that nitrous oxide could induce great enjoyment, he let the English poets Coleridge and Southey try it under his supervision; however, after a period of being « l’objet de l’engouement universel », ‘the object of universally exaggerated admiration’ in England, France, and Germany, it fell slowly into oblivion—but survived among students and physicians « comme un jeu de physique amusante », ‘as an amusing physics game’ (L. Hugounenq, Traité des Poisons [Hygiène Industrielle — Chimie Légale], Lib. Acad. Mèd., Paris, 1891, p. 274). I have no evidence that Giraud used laughing gas (or ether, opium, or hashish) at the Catholic University of Louvain (or later), but at least one of his friends there, Louis Delattre, was a medical student (so would have had easy access to at least the two gaseous intoxicants). However, Giraud greatly admired Théodore de Banville (to whom he dedicated his twelve Rondels Bergamasques in La Revue Moderne, 1882, honoring him as « BON PRINCE DE LA FANTAISIE LYRIQUE »), himself an admirer of Charles Baudelaire, whose drug-taking was well known. And of course rondel XXII suggests Giraud’s openness (practical or theoretical) to psychoactive substances.

3 S’échancre le ciel : No edition of DAf admits a reflexive use of échancrer, « Tailler, évider, couper en dedans en forme de croissant, de portion de cercle », ‘To cut or hollow out into the shape of a crescent or a part of a circle’; nor does the G/HT French corpus reveal any literary uses at all in or before the 19th century—most uses are scientific, a few refer to artisanry, none are figurative. I would credit Giraud with the creation of a novel, highly visual metaphor here.

13 blanche parente : See XIII.1.

Share this post