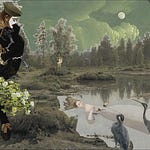

XXI. LUNE MALADE

O Lune, nocturne phtisique, Sur le noir oreiller des cieux, Ton immense regard fiévreux M’attire comme une musique !

Tu meurs d’un amour chimérique, Et d’un désir silencieux, O Lune, nocturne phtisique, Sur le noir oreiller des cieux !

Mais dans sa volupté physique L’amant qui passe insoucieux Prend pour des rayons gracieux Ton sang blanc et mélancolique, O Lune, nocturne phtisique !

XXI. SICK MOON

O Moon, nocturnal consumptive, on the black pillow of the skies, your immense fevered gaze pulls me to you like music!

You’re dying of a chimerical love, and of a silent desire, O Moon, nocturnal consumptive, on the black pillow of the skies!

But wrapped up in corporeal pleasure the lover who passes by without a care mistakes for rays of grace your white, melancholy blood, O Moon, nocturnal consumptive!

NOTES

1 This is the third rondel in RM1883, where it has the same title.

2 nocturne : See VI.6.

phtisique : A consumptive, i.e., a tubercular person. According to M. D. Grmek, Diseases in the Ancient Greek World (English translation by M. and L. Muellner, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1989, of Les maladies à l’aube de la civilisation occidentale: recherches sur la réalité pathologique dans le monde grec pré- historique, archaïque, et classique, Payot, Paris, 1983), p. 183, “In ancient Greek the word phthisis ‘consumption, phthisis’ has a more general sense than the purely medical meaning of its calques in modern languages. When Aristotle speaks of the phthisis of the moon, he simply means that it is waning.” Would Giraud have learned about Aristotle’s φθίσις της σελήνης, the consumption of the moon, during his schooling? In 1882 Koch identified the tubercle bacillus; until then, what R. and J. Dubos (The White Plague: Tuberculosis, Man, and Society, Boston, Little, Brown, 1952, p. 11) call “the perverted attitude of the romantic era toward the disease”—the ascription of various psychological and esthetic characteristics to consumptives, whether as causes, effects, or both, of their disease—pervaded literary and artistic culture. In this rondel Giraud projects that attitude onto the moon; in XXV, he reflects its widespread application to Chopin. According to E. and J. de Goncourt (Watteau [etc.], Paris, E. Dentu, 1860), Watteau suffered « des malades de langueur » ; the current DAf calls maladie de langueur an obsolete term for la phtisie. Did Giraud know Watteau may have been un phtisique?

3 oreiller : The core meanings of E. pillow and F. oreiller are nearly identical: OED defines pillow as “A support for the head when lying or sleeping”; DAf1694 defines oreiller as « Coussin qu’on se met sous la teste quand on est couché », ‘A cushion that one puts under the head when one is abed’. In following editions the only changes are spelling reforms, slight rephrasings, a transient requirement (in DAf1835 and DAf1878) that the cushion be rectangular (noted by the OED for pillow with “esp.”, but never required), and—in the current edition only—the requirements that the covering be fabric and the filling be wool, feathers, hair, or synthetic material (perhaps legal or regulatory concerns rather than lexicography motivate these bizarrely pedantic limitations). The peripheral meanings and over- tones of pillow and oreiller are, however, quite dissimilar. No other English word is at all closely related to pillow (aside from a few derivatives, like pillow-fight or figurative-turned-technical meanings in mechanics, shipbuilding, architecture, etc.); in French, written and spoken alike, oreiller contains oreille, ‘ear’, giving the word a concrete iconicity that pillow can never have had in English.

5 une musique : Littré1884 provides dozens of attributed examples of the phrase; most clearly mean a piece, genre, or performance of music.

6 amour chimérique : Unlike X.12, here the combination of noun and adjective is not paradoxical: sometimes amour really does have no real foundation.

10 In RM1883, commas appear after « Mais » and at the end of the line.

11 In RM1883, commas appear after « passe » and at the end of the line.

12 rayons : See XLII.13.

13 sang blanc : Literally, white blood. Up-to-date schoolbooks for Giraud’s generation (e.g., Lambert, Zoologie, à l’usage des lycées [etc.], Paris, F. Savy, 1865, p. 56) taught that Aristotle’s distinction between red-blooded animaux à sang rouge (viz., verte- brates and some annelid worms) and bloodless animaux exsangues (invertebrates and other worms) had been superseded, with animaux à sang blanc as the new term for the latter. On the other hand, no later than de Lassus’s prize-winning Disserta- tion sur la Lymphe [etc.] (Lambert, Paris, 1744), physiologists had begun to use sang blanc for lymph; A. Wahlen’s popularizing Nouveau dictionnaire de la conversation [etc.] (Bruxelles, Librairie-Historique-Artistique, 1845) had an article on Lymphe subtitled Sang blanc. Some sources claim Hippocrates wrote of ‘white blood’; but sang blanc is nowhere in Littré’s Œuvres complètes d’Hippocrate (Paris, Baillière, 1839–1861).

Share this post