L. CRISTAL DE BOHÊME

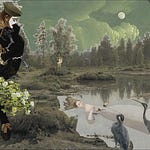

Un rayon de lune enfermé Dans un beau flacon de Bohême, Tel est le féerique poème Que dans ces rondels j’ai rimé.

Je suis en Pierrot costumé, Pour offrir à celle que j’aime Un rayon de lune enfermé Dans un beau flacon de Bohême.

Par ce symbole est exprimé,

O ma très chère, tout moi-même :

Comme Pierrot, dans son chef blême,

Je sens, sous mon masque grimé,

Un rayon de lune enfermé.

L. BOHEMIAN CRYSTAL

A ray of moonlight trapped in a beautiful bottle of crystal glass, such is the enchanted poem that I have composed in these rondels. I wear Pierrot as my costume, to offer to her that I love a ray of moonlight trapped in a beautiful bottle of crystal glass. By this symbol is expressed, O my most beloved, my whole self: like Pierrot, wearing his pallid head, I feel, beneath my old man’s mask, a ray of moonlight, trapped.

NOTES (by line number, starting with the title)

1 This is rondel XII, otherwise untitled, in Rondels Bergamasques.

CRISTAL : In physics, chemistry, and mineralogy, a ‘crystal’ is solid matter in which the constituent atoms are spatially organized in one of a very few regular manners. Glass, in the vernacular sense, is never crystalline in the sense of those disciplines. (Physicists also define ‘glass’ in a technical, mathematically precise way that does cover vernacular glass as well as some more exotic substances, while distinguishing it from other kinds of amorphous solids.) ‘Crystal glass’, so called, is any of several related types of vernacular glass that (at least to the lay eye) share some of their properties with ‘rock crystal’, the pure (and therefore colorless) form of the mineral quartz. According to the OED, “In ancient and medieval thought (rock) crystal was surmised to be congealed water or ice ‘petrified’ by some long-continued natural process. There was thus no transfer of sense involved in applying to it the same name as to clear ice, of which it was viewed as merely another state.” (That “same name” was κρύσταλλος in Ancient Greek, whence crystallus in Classical Latin.) According to C. Laboulaye, Dictionnaire des Arts et Manufactures [etc.], vol. 2 (Paris, 1870), « Le verre de Bohême est un verre à base de potasse et de chaux, remarquable par sa beauté, sa dureté et ses autres qualités, qui lui ont fait donner le nom de cristal de Bohême, pour le distinguer du cristal ordinaire à base de plomb », ‘Bohemian glass is a glass made of potash and lime, remarkable for its beauty, its durability, and its other qualities, which have given it the name Bohemian crystal, to distinguish it from ordinary crystal [glass] made with lead’. (Among the “other qualities” of cristal de Bohême are that it mimics the reflective and refractive properties of natural ‘rock crystal’, i.e., colorless quartz, yet unlike quartz can be easily worked and artificially colored.) True crystals can be either natural or artificial; ‘crystal glass’ is not found in nature (see the note on gangue, XXV.6).

BOHÊME : Note that Bohême and bohème are distinct (though obviously very closely related) French words: the first is a proper noun denoting either a geographical entity or a member of certain groups of persons associated with that entity (by ancestry, residence, citizenship, etc.), with adjectival form Bohémien, Bohémienne (note the change of the diacritic from circumflex to acute); the second is an adjective or a common noun describing a certain way of life or denoting someone who lives it (see XLVIII.13). Their English translations are, respectively, ‘Bohemia’ (with adjectival form ‘Bohemian’) and ‘bohemian’ (a noun that is its own adjectival form). These are not false friends (IV.12), they are false conjoined twins or triplets!

4 féerique : See II.4.

6 en Pierrot costumé : French costumé en is English ‘dressed as’ (clear from DAf example sentences for costumer from 1835 to the present), so the idiomatic meaning of « Je suis en Pierrot costumé » is simply ‘I am dressed as [a] Pierrot, I am wearing the costume of [a] Pierrot’. I propose, however, that Giraud (also) means ‘I wear (the character, the body of) Pierrot as my costume, I inhabit Pierrot.’

12 chef : The primary definition in DAf1878 is « Tête. Il ne se dit guère maintenant, au propre, qu’en parlant De reliques », ‘Head, nowadays scarcely used in its literal sense except in speaking Of holy relics’. DAf1878 comments further that « Il s’emploie quelquefois dans la poésie badine », ‘It is sometimes used in light [or light-hearted] verse’. I think it is fair to assume that those statements, and the one following, describe Giraud’s usage here.

blême : DAf1878, « Pâle. On ne le dit guère que Du visage, du teint », ‘Pale. Hardly used except Of the face, of the complexion’.

13 grimé : Past participle of grimer, « T. de Théâtre. Se peindre des rides sur le visage, et prendre les airs et les manières convenables pour représenter un vieillard, une duègne, etc. », ‘Theatrical term. To paint wrinkles on one’s face, and employ appropriate attitudes and behaviors to portray an old man, a old woman, or the like’ (DAf1878); Picoche derives grimer from the 18th century proper name Grime, one particular such « vieillard ridicule », ‘ridiculous old man’. Of the 500 lines of poetry (not counting refrains) in Pierrot Lunaire, only this one even suggests that the poet, his narrator, or either of his alter egos Pierrot and Arlequin, is—or has made himself up to be—an old man, ridiculous or otherwise. When this rondel first appeared in print, Albert Giraud was 22 years old.

Share this post